Columnar databases store data by column rather than by row, fundamentally changing how analytical queries access information. Instead of reading entire records to extract a few fields, columnar storage allows query engines to scan only the columns they need, reducing I/O by orders of magnitude for analytical workloads.

But that simple definition barely scratches the surface. Columnar storage has evolved through four decades of innovation, from batch-oriented data warehouses to real-time systems handling 10,000+ dynamic columns from AI agents and IoT devices. This guide draws on experience building Apache Doris, a real-time OLAP engine powering analytics at Xiaomi, Baidu, and thousands of other companies. It explains not just what columnar databases are, but why they keep reinventing themselves, and helps you identify which generation of columnar technology fits your use case.

The Evolution of Columnar Storage

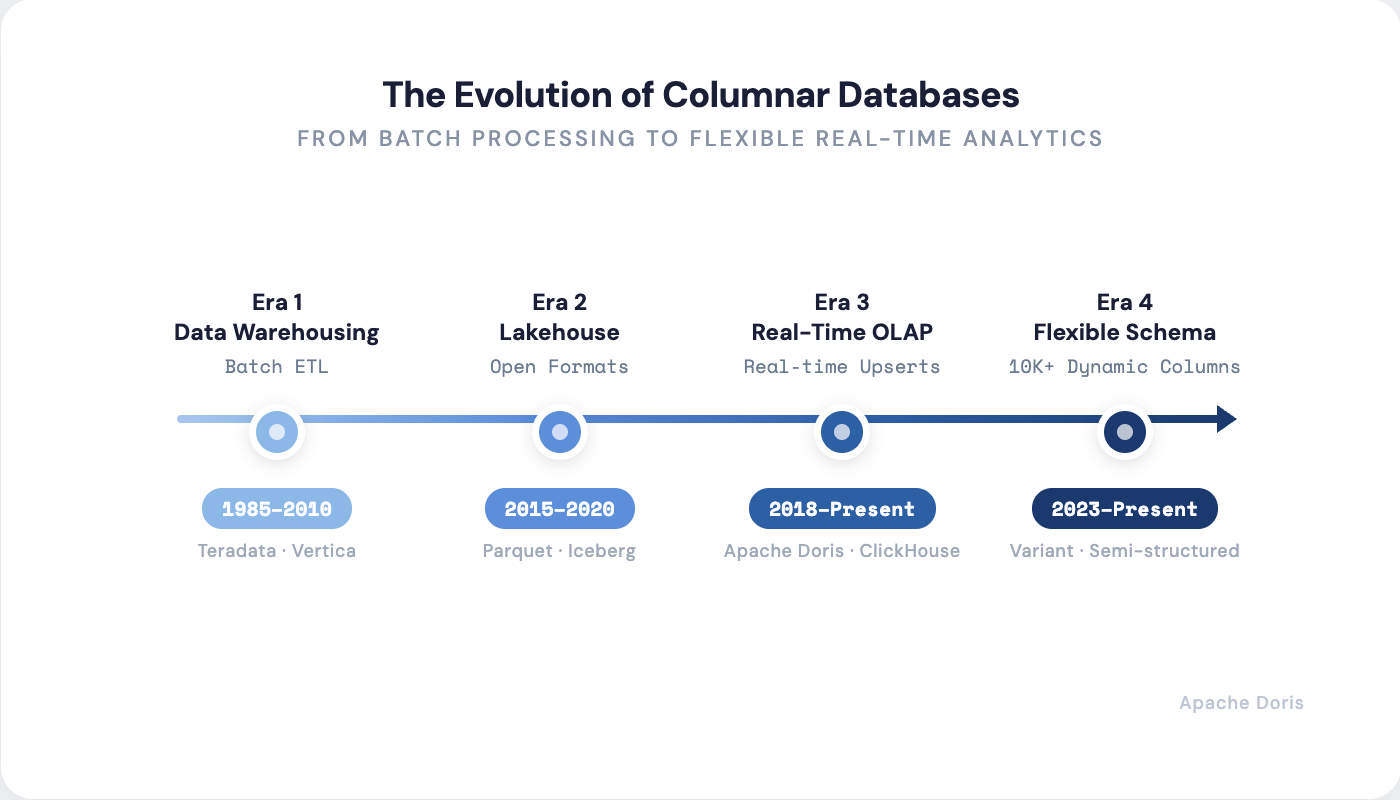

Columnar databases are not a single invention. They are the result of four decades of continuous reinvention. Each era solved a specific problem that the previous generation couldn't handle.

Columnar databases are not a single invention. They are the result of four decades of continuous reinvention. Each era solved a specific problem that the previous generation couldn't handle.

Era 1: Data Warehousing (1985–2010) — The Foundation

By the mid-1980s, businesses were drowning in data they couldn't analyze. Transactional databases (OLTP systems) were optimized for inserting and updating individual records, not for answering questions like "What were total sales by region last quarter?" Running analytical queries on production databases meant slow queries, locked tables, and frustrated DBAs.

In 1985, George Copeland and Setrag Khoshafian published "A Decomposition Storage Model" that asked a simple question: what if we stored data by column instead of by row?

The insight was elegant. When a business analyst runs SELECT region, SUM(sales) FROM orders GROUP BY region, they don't need the customer name, shipping address, or order notes. A row-based database must read entire rows, wasting I/O on columns that will be immediately discarded. A column-based layout reads only the two columns needed.

Twenty years later, Michael Stonebraker and his team formalized these ideas in the landmark C-Store paper (2005), which became the foundation for Vertica and influenced every modern analytical database.

Era 2: The Lakehouse (2015–2020) — Unification

The 2010s created a data architecture split personality. Data lakes stored anything cheaply but queried terribly. Data warehouses queried fast but required expensive ETL pipelines. Organizations maintained both, paying for redundant storage and battling consistency issues.

The lakehouse architecture emerged to unify these worlds through open columnar file formats (Parquet, ORC) and open table formats (Iceberg, Delta Lake, Hudi). These formats brought ACID transactions, schema evolution, and time travel to cheap object storage.

Era 3: Real-Time OLAP (2018–Present) — Speed Meets Freshness

Modern applications don't wait for nightly batch jobs. Fraud detection must analyze transactions in milliseconds. Operational dashboards need to show metrics as they happen. User-facing analytics must respond in under a second for millions of concurrent users.

A new generation emerged: ClickHouse, Apache Doris, and Apache Pinot. These systems combine columnar storage with real-time upserts, vectorized execution processing batches of thousands of values simultaneously, and hybrid row-column storage achieving 30,000+ queries per second for point lookups.

Era 4: Flexible Schema Analytics (2023–Present) — The AI-Native Frontier

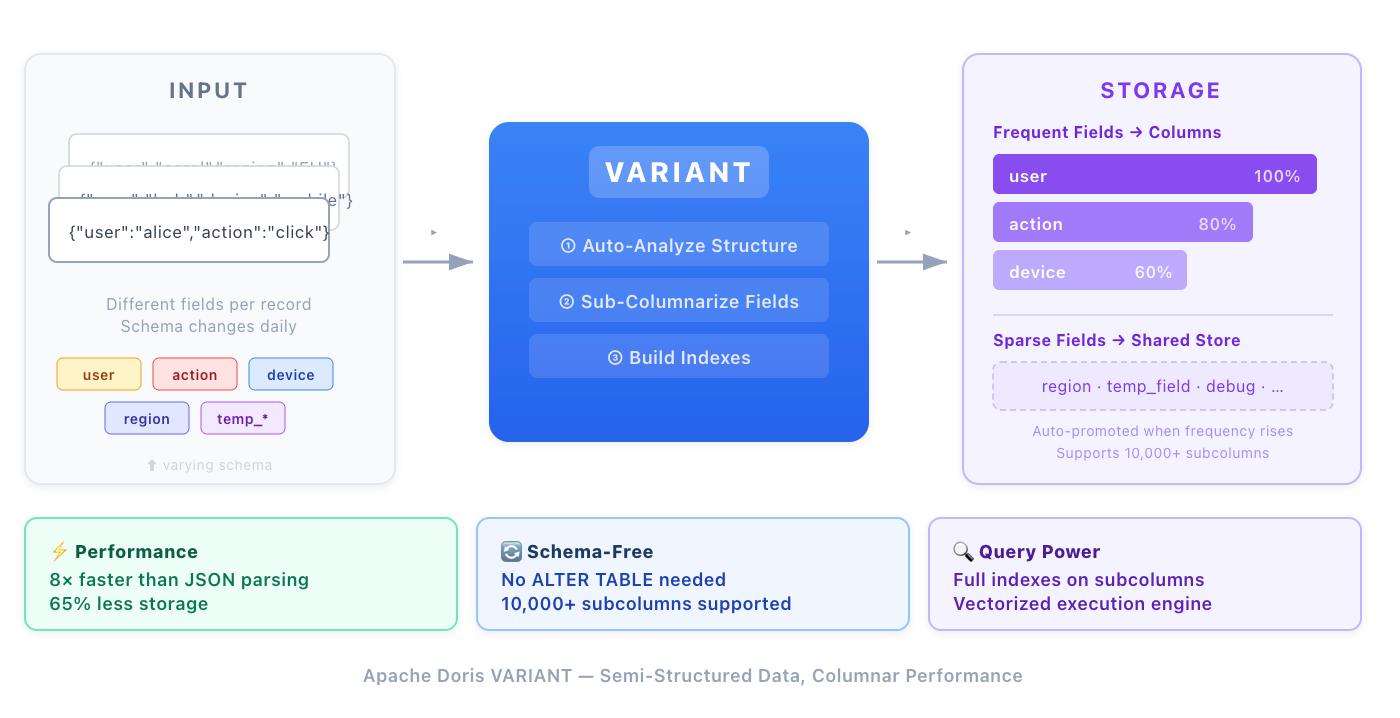

AI agents and IoT devices generate JSON with unpredictable schemas, sometimes containing 10,000+ unique fields. Traditional columnar databases choke on metadata bloat and schema rigidity. Modern systems like Apache Doris introduced the VARIANT data type, automatically subcolumnarizing frequent JSON paths while handling sparse fields efficiently.

How Columnar Databases Work

Understanding columnar storage requires examining four key mechanisms that work together to deliver performance.

Column-Based Data Storage Layout

In a row-oriented database, a table like this:

| id | name | age | city |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Alice | 30 | NYC |

| 2 | Bob | 25 | LA |

| 3 | Carol | 35 | NYC |

Is stored on disk as:

[1, Alice, 30, NYC] [2, Bob, 25, LA] [3, Carol, 35, NYC]

A columnar database stores the same data as:

[1, 2, 3] [Alice, Bob, Carol] [30, 25, 35] [NYC, LA, NYC]

This layout means a query like SELECT AVG(age) FROM users reads only the age column, not the entire table. For a table with 100 columns where you need 3, that's a 97% reduction in I/O.

File layout strategies matter for cloud costs:

| Strategy | Description | Trade-off |

|---|---|---|

| All columns in one file (Parquet, ORC) | Columns stored together in row groups | One S3 PUT per write (~$5/million); atomic writes |

| One column per file | Each column stored separately | N columns = N PUT requests; 10x+ cloud cost |

Modern formats like Parquet use the single-file approach with internal columnar organization, balancing query efficiency with cloud storage economics.

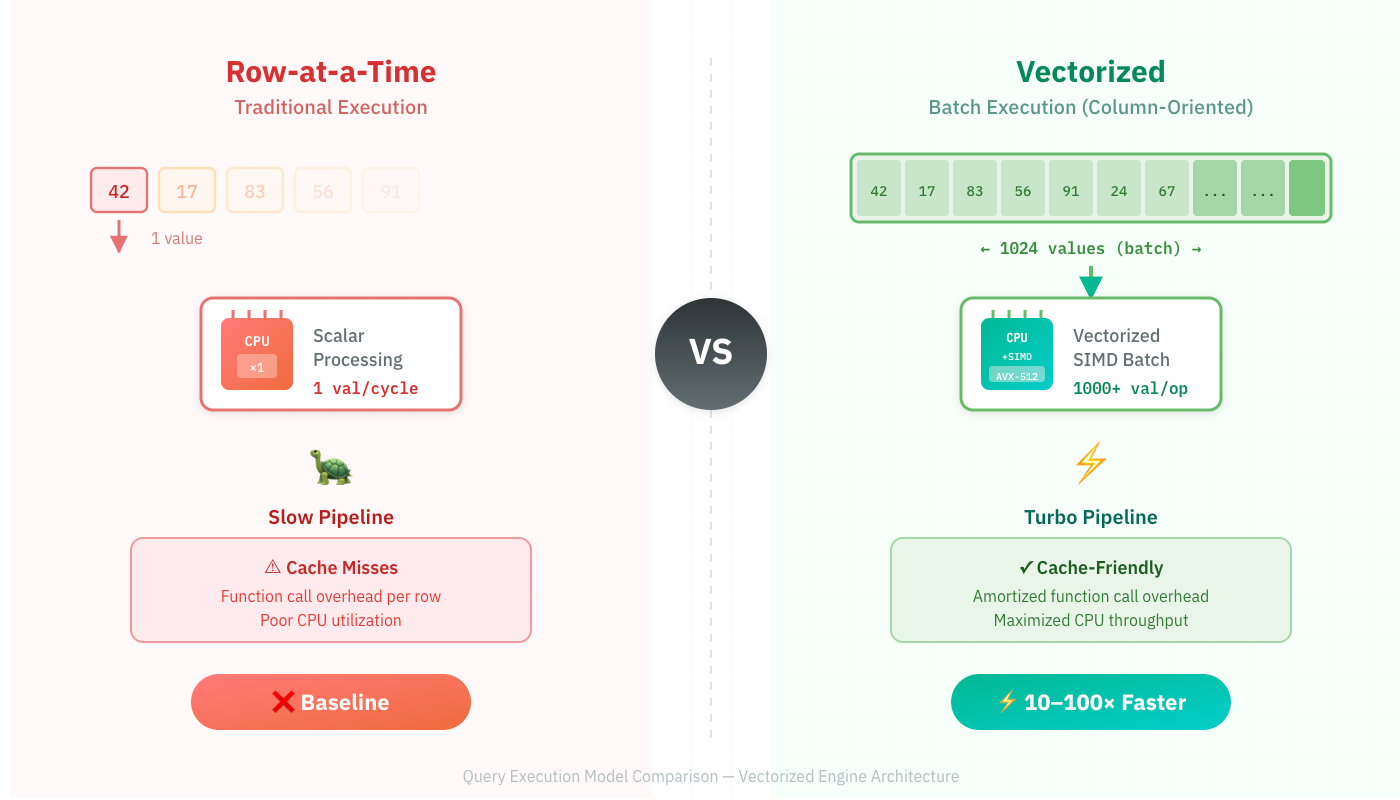

Vectorized Query Execution

Traditional databases process one row at a time using the "Volcano" iterator model. For each row, the CPU fetches instructions, processes one value, and moves to the next. This pattern destroys CPU cache efficiency and leaves most of the processor's power unused.

Traditional databases process one row at a time using the "Volcano" iterator model. For each row, the CPU fetches instructions, processes one value, and moves to the next. This pattern destroys CPU cache efficiency and leaves most of the processor's power unused.

Vectorized execution, pioneered in the MonetDB/X100 paper (2005), processes batches of 1,000–4,000 values simultaneously. The CPU loads a vector of values, applies the same operation to all of them using SIMD instructions, and moves to the next batch.

The impact is dramatic. The MonetDB paper demonstrated order-of-magnitude speedups, and the technique now powers Snowflake, DuckDB, ClickHouse, and nearly every modern analytical engine. The paper won CIDR's Test of Time Award. Its influence cannot be overstated.

Compression and Encoding Techniques

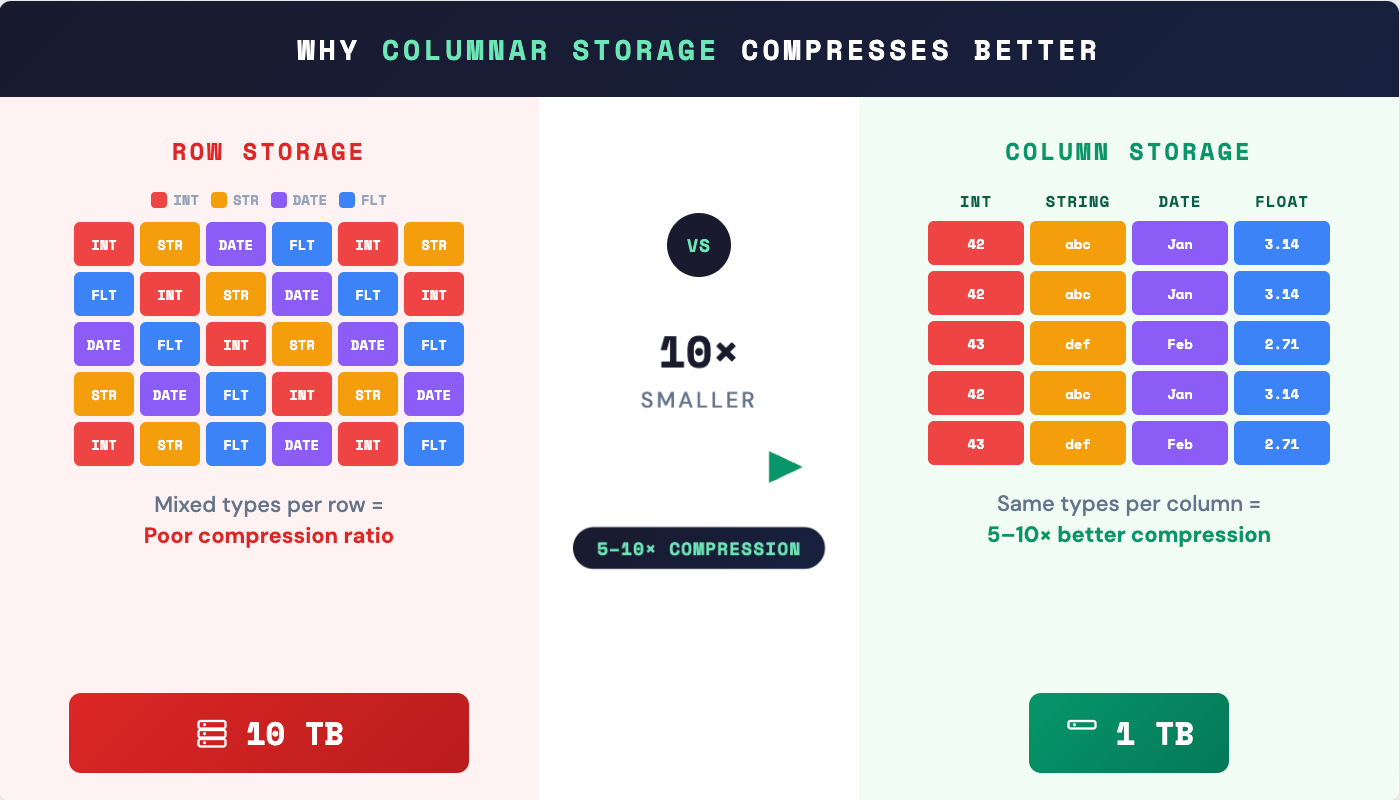

Columnar storage enables compression techniques that row storage cannot match. When similar values are stored together, patterns emerge that compression algorithms exploit.

Columnar storage enables compression techniques that row storage cannot match. When similar values are stored together, patterns emerge that compression algorithms exploit.

| Technique | How It Works | Best For |

|---|---|---|

| Dictionary encoding | Replace repeated strings with integer codes | Low-cardinality columns (country, status) |

| Run-length encoding (RLE) | Store "value + count" instead of repeating | Sorted columns, consecutive duplicates |

| Bit-packing | Use minimum bits needed for value range | Integer columns with limited range |

| Delta encoding | Store differences between consecutive values | Timestamps, monotonic sequences |

| Frame-of-reference | Store offset from a base value | Clustered numeric values |

The Abadi et al. paper on compression (2006) showed that integrating compression with query execution (operating directly on compressed data) yields additional performance gains. Modern columnar databases typically achieve 5–10x compression ratios compared to row storage.

Late Materialization and Column Pruning

"Materialization" refers to constructing complete rows from individual columns. Traditional query execution materializes rows early, immediately assembling full tuples to pass through the query plan.

Late materialization delays this assembly as long as possible, operating on individual columns throughout most of query execution. The Abadi et al. paper on materialization strategies (2007) demonstrated up to 10x performance improvement from this technique.

Why late materialization helps:

- Fewer tuples constructed: Filters reduce the dataset before row assembly

- Cache efficiency: Columnar data fits better in CPU cache

- Compression benefits preserved: Data stays compressed longer

- Column pruning: Columns not in the final result are never read

Modern query optimizers combine column pruning (reading only needed columns) with predicate pushdown (applying filters at the storage layer) to minimize data movement.

Columnar Databases vs Row-Oriented Databases

The choice between columnar and row-oriented storage isn't about which is "better." It's about matching storage layout to access patterns.

Row-Oriented Databases

Row storage keeps all fields of a record together on disk. This layout optimizes for:

- Transactional workloads: Inserting, updating, or deleting complete records

- Point queries: Retrieving one record by primary key

- Full-record access: SELECT * FROM users WHERE id = 123

Strengths:

- Fast single-record operations

- Efficient for workloads that access entire rows

- Lower write amplification for updates

Columnar Databases

Column storage separates each attribute into its own data structure. This layout optimizes for:

- Analytical workloads: Aggregations, groupings, scans over large datasets

- Selective column access: Queries touching few columns of wide tables

- Compression: Similar values grouped together compress well

Strengths:

- Orders-of-magnitude faster for analytical queries

- Dramatic compression (5–10x typical)

- Efficient use of I/O bandwidth and CPU cache

Key Differences in Storage, Queries, and Performance

| Aspect | Row-Oriented | Columnar |

|---|---|---|

| Storage layout | Row-by-row | Column-by-column |

| Read pattern | Reads entire rows | Reads only needed columns |

| Write pattern | Append/update rows efficiently | Write amplification for updates |

| Compression | Limited (mixed data types per block) | Excellent (homogeneous data per block) |

| Best for | OLTP, transactions | OLAP, analytics |

| Query: SELECT * | Fast | Slow (must reassemble rows) |

| Query: SELECT a, SUM(b) | Slow (reads all columns) | Fast (reads only a, b) |

| Concurrency model | High-QPS single-row ops | Lower-QPS complex queries |

The Hybrid Reality

Modern databases increasingly blur these boundaries:

Modern databases increasingly blur these boundaries:

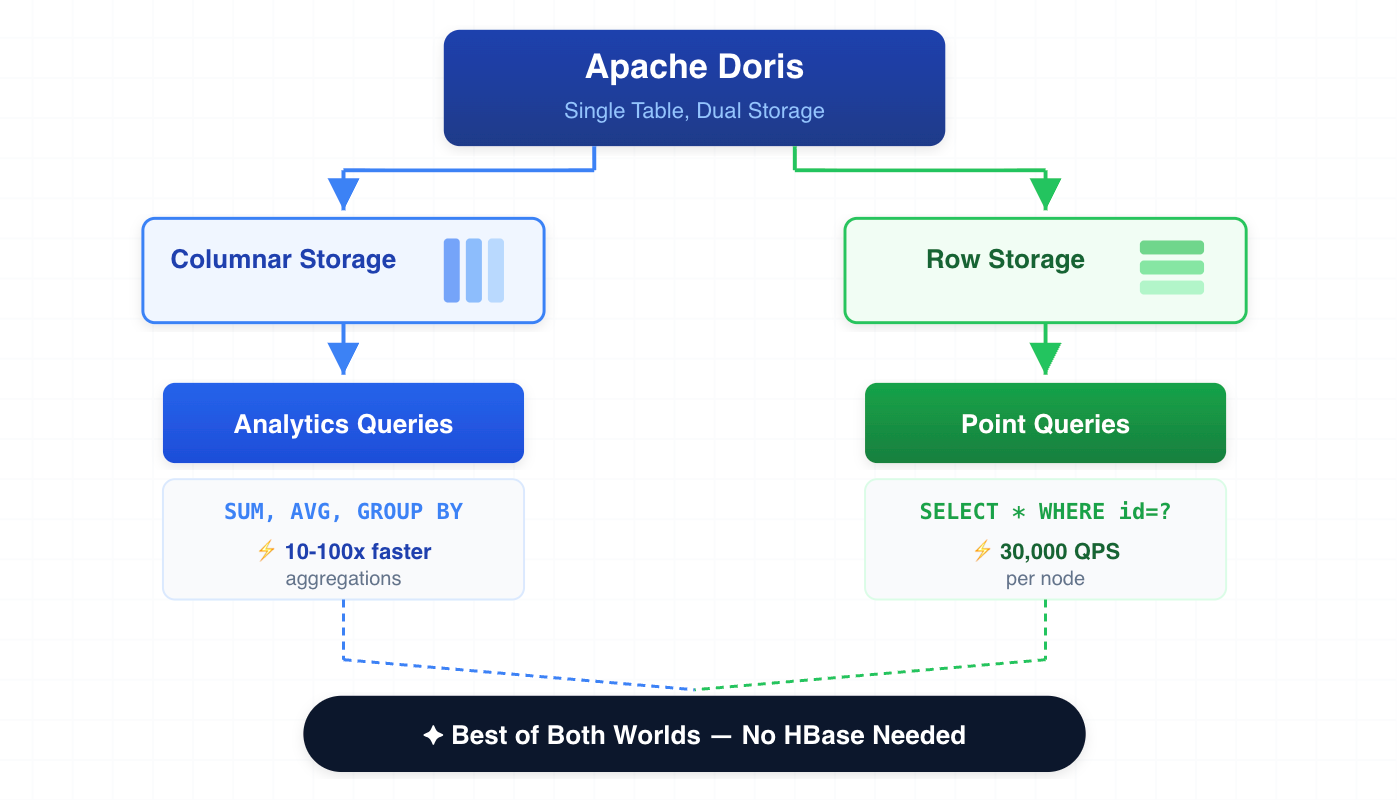

- Apache Doris offers optional row storage alongside columnar for point queries

- SQL Server supports both row and column stores in the same table

- SingleStore (formerly MemSQL) provides row and columnar storage tiers

- TiDB implements HTAP with row-based TiKV and columnar TiFlash

The 2024 HTAP survey documents how hybrid transactional/analytical processing is becoming mainstream, combining row and column storage to serve both workload types without data duplication.

Benefits of Columnar Databases

Columnar databases are not faster simply because they “store data by column.” Their performance advantage comes from a set of reinforcing design choices—column pruning, compression, vectorized execution, and parallelism—that compound as data volume grows. The benefits below reflect what teams typically observe in production once workloads move beyond small datasets and simple queries.

1. Query Performance

Columnar databases routinely deliver 10–100x speedups for analytical queries compared to row stores. The gains compound:

- Read only the columns you need (I/O reduction)

- Compress data more effectively (further I/O reduction)

- Process data in vectors (CPU efficiency)

- Apply predicates early (filter before expensive operations)

2. Storage Efficiency

Dictionary encoding, run-length encoding, and type-specific compression typically achieve 5–10x compression ratios. A 10 TB dataset in PostgreSQL might occupy 1–2 TB in ClickHouse.

For cloud deployments, this translates directly to cost savings. On Athena (50 to $5 per terabyte of source data.

3. I/O Optimization

Modern analytical queries often touch less than 5% of available columns. Columnar storage ensures you pay only for what you use. Combined with predicate pushdown and partition pruning, queries typically scan 1-5% of physical data when touching 3-5 columns of a 100-column table.

4. Cache Efficiency

Columnar data packs more useful values into each cache line. When processing a column of integers, the CPU cache contains only integers, not interleaved strings, timestamps, and other fields that won't be used.

5. Parallelization

Columnar layouts naturally partition work across cores and nodes. Different columns can be processed independently, and vectorized operations map directly to SIMD parallelism within each core.

6. Schema Evolution

Modern columnar formats (Parquet with Iceberg/Delta) support adding, removing, and renaming columns without rewriting existing data. The VARIANT type in Apache Doris takes this further, handling schema-on-read for semi-structured data.

Limitations and Challenges of Columnar Databases

No storage layout is perfect. Understanding columnar limitations helps you choose the right tool.

1. Poor Point Query and Random Access Performance

Columnar storage excels at sequential scans but struggles with random row access. Fetching a single row requires reading from N separate column files, one I/O per column.

Impact: A SELECT * FROM users WHERE id = 12847 on a 500-column table requires 500 I/O operations.

Mitigations emerging:

- Hybrid row-column storage (Apache Doris): Store row data alongside columns, achieving 30,000 QPS for point queries

- New file formats (Lance, Vortex): 100–1000x faster random access than Parquet through adaptive encodings and zero-copy reads

2. Write Amplification for Updates

Updating a single field in a row-oriented database touches one page. In a columnar database, the same update might touch multiple column files, requiring compaction to maintain query performance.

Impact: Heavy update workloads can overwhelm compaction, degrading read performance.

Mitigations:

- Merge-on-Write with delete bitmaps: Apache Doris uses a mark-delete approach where updates mark old rows as deleted and write new versions. This avoids costly in-place modifications while maintaining read performance

- Merge-on-Read: Updates written as deltas, merged during queries. This provides lower write latency, but queries must merge versions

3. The Wide Table Problem (1,000–10,000+ Columns)

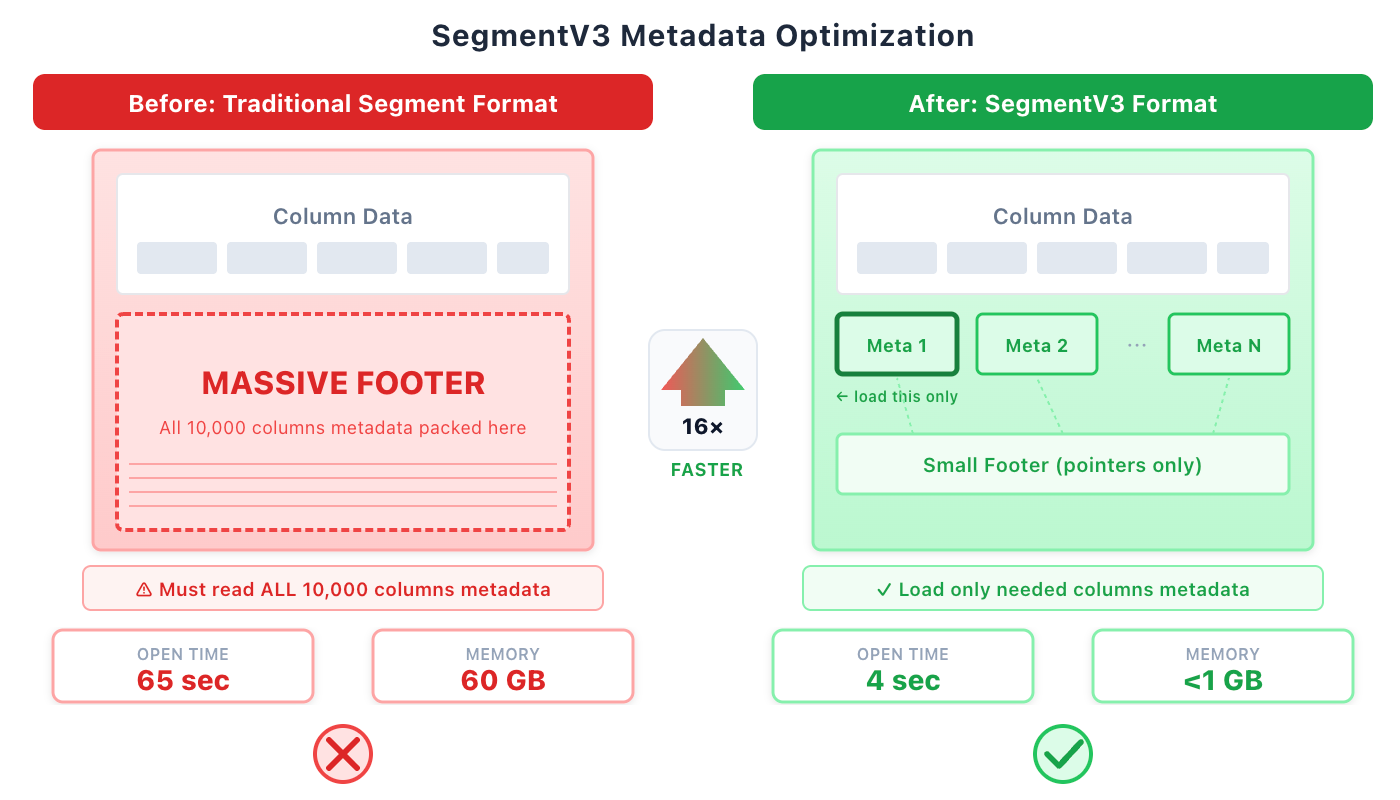

Traditional columnar formats store all column metadata in a single "footer" at the end of each file. For narrow tables (10–100 columns), this works fine. For wide tables common in log analytics and user profiling (1,000–10,000+ columns), metadata bloat becomes crippling.

Traditional columnar formats store all column metadata in a single "footer" at the end of each file. For narrow tables (10–100 columns), this works fine. For wide tables common in log analytics and user profiling (1,000–10,000+ columns), metadata bloat becomes crippling.

Impact:

- Multi-megabyte footers to parse before reading any data

- Memory spikes loading metadata (up to 60 GB for extreme cases)

- File open times measured in minutes, not milliseconds

Mitigations:

- Apache Doris SegmentV3: Decouples column metadata from footer; stores in separate index pages. Result: file open reduced from 65 seconds to 4 seconds.

- LanceDB: No row groups; O(1) column access via FlatBuffer metadata

- Vortex: FlatBuffer metadata designed for ultra-wide schemas

4. Schema Rigidity

Traditional columnar systems require schema definition upfront. Every new field from IoT devices or AI agents requires

Traditional columnar systems require schema definition upfront. Every new field from IoT devices or AI agents requires ALTER TABLE ADD COLUMN, which becomes impractical when schemas change daily.

Impact: Forces preprocessing pipelines to normalize data, adding latency and complexity.

Mitigations:

- VARIANT type: Auto-subcolumnarizes JSON fields; handles 10,000+ dynamic columns

- Schema-on-read approaches in lakehouse formats

5. Row Reconstruction Overhead

Queries that need complete rows (SELECT *) must gather data from all column files and reassemble tuples. This is exactly the opposite of columnar's strength.

Impact: Full-row retrievals can be slower than row-oriented databases.

Mitigation: Use columnar databases for analytical patterns; consider hybrid storage for mixed workloads.

6. Higher Memory Requirements

Vectorized processing and late materialization require buffering columns in memory. Decompression and query processing can spike memory usage.

Impact: Columnar databases often need more RAM per query than row stores.

Mitigation: Careful memory budgeting; spill-to-disk for large intermediates.

When Should You Use a Columnar Database?

Columnar databases excel when your workload matches their strengths:

Ideal Use Cases

Business Intelligence and Reporting

- Dashboards aggregating millions of rows

- Ad-hoc queries from analysts exploring data

- Scheduled reports computing metrics across large datasets

Log and Event Analytics

- Application logs, security events, clickstreams

- High-volume ingestion (millions of events/second)

- Queries filtering by time range and aggregating by dimensions

Real-Time Operational Analytics

- Monitoring dashboards with sub-second refresh

- Metrics aggregation for SRE/DevOps

- User-facing analytics (usage dashboards, embedded analytics)

Data Warehousing and Data Lakes

- Historical analysis across years of data

- Complex joins across fact and dimension tables

- ETL/ELT pipelines producing aggregated views

Machine Learning Feature Engineering

- Computing features across large datasets

- Time-series aggregations for training data

- Batch scoring pipelines

Semi-Structured Data Analytics (with modern systems)

- JSON logs from AI agents and IoT devices

- Observability data with dynamic tags

- Event streams with evolving schemas

When Should You Avoid a Columnar Database?

Columnar databases excel at analytics, but they can be the wrong choice for OLTP-heavy workloads, point lookups, or small datasets where simplicity matters more than scan performance.

Transactional Workloads (OLTP)

If your primary operations are:

- Inserting individual records at high frequency

- Updating specific fields in existing records

- Deleting and re-inserting records

- Requiring strict transactional guarantees across operations

Use a row-oriented database (PostgreSQL, MySQL, SQL Server).

Primary Key Lookups at Scale

If your dominant query pattern is fetching single records by ID (like a cache or key-value store), consider:

- Redis or Memcached for caching

- DynamoDB or Cassandra for distributed key-value

- PostgreSQL with proper indexing

Note: Modern columnar databases with hybrid row storage can handle high-QPS point queries. Evaluate benchmarks for your specific pattern.

Small Datasets

For datasets under 10 GB, the overhead of columnar systems (cluster deployment, learning curve) often exceeds their benefits. SQLite, PostgreSQL, or even pandas may be simpler and equally fast.

Examples of Columnar Databases

The columnar landscape spans open-source projects, cloud services, and embedded engines.

Open-Source Real-Time OLAP

*Apache Doris* / *VeloDB*

- Real-time customer-facing analytics with sub-second latency

- VARIANT type for 10,000+ column semi-structured data

- Hybrid row-column storage for 30,000 QPS point queries

- MySQL-compatible interface

- Extremely fast for time-series and log analytics

- Extensive compression and encoding options

- Strong community and ecosystem

- User-facing real-time analytics

- Designed for high-concurrency, low-latency

- Powers LinkedIn's analytics

Cloud Data Warehouses

- Fully managed, elastic scaling

- Separation of storage and compute

- Strong SQL and data sharing capabilities

- Serverless, pay-per-query model

- Petabyte-scale analytics

- ML and geospatial built-in

- Tight AWS integration

- Columnar storage with query optimization

- Redshift Spectrum for data lake queries

- Lakehouse architecture on Delta Lake

- Unified with ML and data engineering

- Photon vectorized engine

Embedded and In-Process

*DuckDB*

- In-process analytical database (like SQLite for OLAP)

- Excellent for local analysis and data pipelines

- Zero dependencies, single binary

- Query engine library in Rust

- Foundation for building custom analytical systems

- Arrow-native processing

Emerging Formats

*Lance*

- Columnar format optimized for ML/AI workloads

- 100x faster random access than Parquet

- Native vector search support

*Vortex*

- Next-generation columnar format

- 100–200x faster random access

- Cascading compression with adaptive encoding

Can Columnar and Row-Based Databases Be Used Together?

Absolutely. Increasingly, this is the recommended architecture.

Hybrid Architectures

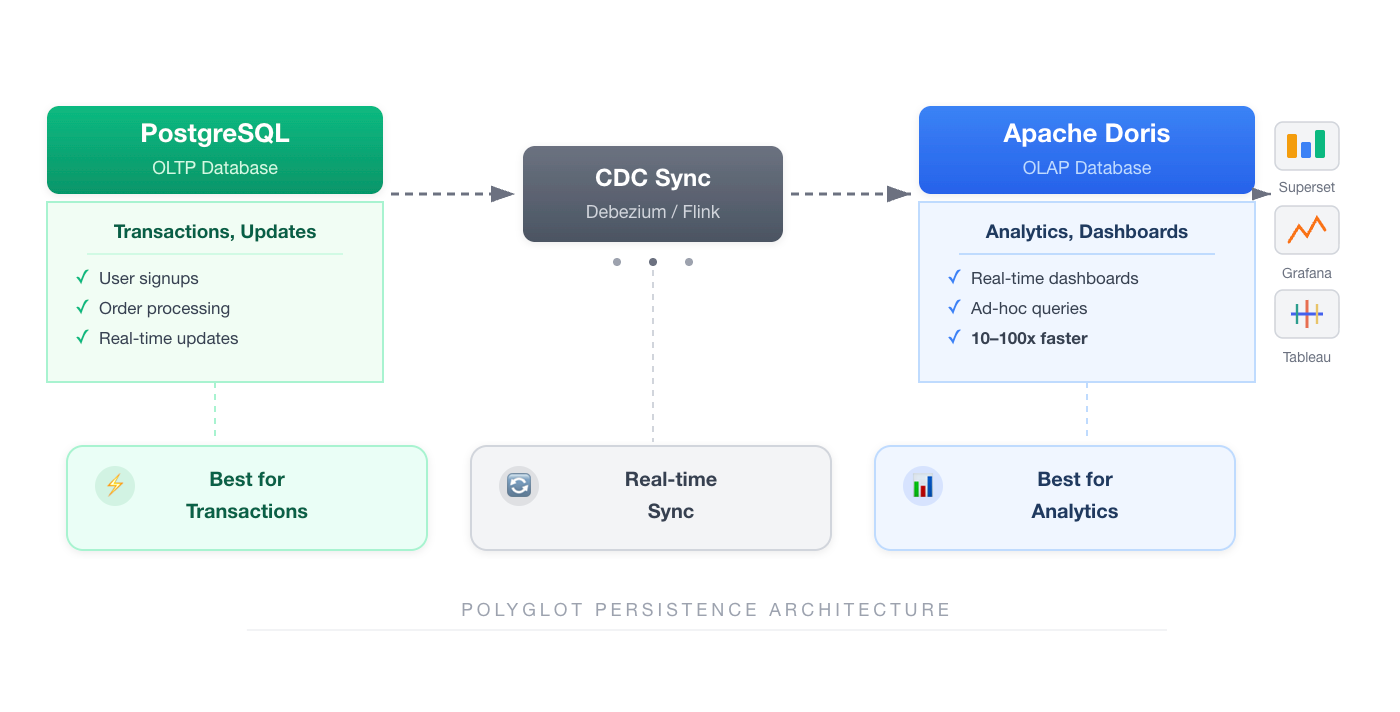

Polyglot persistence: Use row stores (PostgreSQL, MySQL) for transactional workloads and columnar stores (ClickHouse, Doris) for analytics. Sync data via CDC (Change Data Capture) pipelines.

Polyglot persistence: Use row stores (PostgreSQL, MySQL) for transactional workloads and columnar stores (ClickHouse, Doris) for analytics. Sync data via CDC (Change Data Capture) pipelines.

HTAP (Hybrid Transactional/Analytical Processing): Some databases support both workloads natively:

- Apache Doris with hybrid row-column storage

- TiDB with TiKV (row) + TiFlash (column)

- SingleStore with row and columnstore tables

- SQL Server with columnstore indexes on row tables

Within a Single System

Apache Doris demonstrates how row and column storage coexist:

CREATE TABLE user_profiles (

user_id BIGINT,

name STRING,

preferences VARIANT, -- Semi-structured, auto-columnarized

...

) PROPERTIES (

"store_row_column" = "true" -- Also store rows for point queries

);

This table supports:

- Analytical queries: Columnar storage for fast aggregations

- Point queries: Row storage for 30,000 QPS lookups

- Flexible schema: VARIANT for dynamic JSON fields

Choosing Your Architecture

| Scenario | Recommended Approach |

|---|---|

| Separate teams, separate systems | Polyglot: Row store + Columnar store with CDC |

| Single platform, mixed workloads | HTAP database with hybrid storage |

| Analytics on transactional data | Materialized views or real-time sync to columnar |

| Semi-structured + structured | Columnar with VARIANT type |

Frequently Asked Questions About Columnar Databases

How is a columnar database different from a relational database?

Columnar and relational are orthogonal concepts. "Relational" describes the data model (tables with rows and columns, SQL queries, relationships via keys). "Columnar" describes the storage layout (how data is physically organized on disk).

Most columnar databases are relational. They support SQL, tables, joins, and standard relational semantics. The difference is implementation: data is stored column-by-column rather than row-by-row, which optimizes for analytical queries.

Think of it like this: a relational database can be row-oriented (PostgreSQL, MySQL) or column-oriented (ClickHouse, Doris). The relational model is the interface; the storage layout is the implementation.

Are columnar databases suitable for real-time analytics?

Yes. Modern columnar databases are specifically designed for real-time analytics. Systems like Apache Doris and ClickHouse support:

- Real-time ingestion: Data queryable within seconds of arrival

- Real-time upserts: Update existing records without full table rewrites

- Sub-second query latency: Interactive dashboards and user-facing analytics

- High concurrency: Thousands to tens of thousands of queries per second

The key is choosing a columnar database designed for real-time workloads, not a batch-oriented data warehouse.

Do columnar databases support SQL?

Yes. Nearly all columnar databases support SQL as their primary query interface, often with extensions for analytics:

- Window functions for time-series analysis

- Approximate aggregations (HyperLogLog, quantiles) for large datasets

- Array and map types for semi-structured data

- User-defined functions for custom logic

Compatibility varies: cloud warehouses often have their own SQL dialects with standard ANSI SQL as a common base.

Do I have to choose between columnar and row-based databases?

No. Modern architectures commonly use both:

- Row store for transactions (PostgreSQL, MySQL): Handle user signups, orders, updates

- Columnar store for analytics (Doris, ClickHouse): Power dashboards, reports, ad-hoc queries

- CDC pipeline (Debezium, Flink): Sync changes from row store to columnar store in real-time

Alternatively, HTAP databases with hybrid row-column storage serve both workloads in a single system. This involves trade-offs compared to specialized engines, but simplifies operations.

What compression ratio can columnar databases achieve?

Typical compression ratios range from 5:1 to 10:1 compared to uncompressed row storage. Highly repetitive data (status codes, country fields) can achieve 20:1 or higher. Factors affecting compression:

- Data cardinality: Low-cardinality columns (status codes, countries) compress extremely well

- Data ordering: Sorted data enables run-length encoding

- Data types: Integers and timestamps compress better than arbitrary strings

- Encoding choices: Dictionary encoding, delta encoding, bit-packing

A 10 TB PostgreSQL database might occupy 1-2 TB in a columnar database. That's significant savings for both storage costs and query performance.

How do columnar databases handle updates and deletes?

This is where columnar databases have historically struggled, but modern systems offer several strategies:

Merge-on-Write (MoW) with Delete Bitmaps: The approach used by Apache Doris for real-time upserts. Instead of modifying data in place (expensive for columnar), updates mark old rows as deleted via bitmaps and write new versions. This preserves columnar storage benefits while enabling efficient updates. Queries simply skip marked rows.

Merge-on-Read (MoR): Updates written as delta files, merged during queries. Lower write latency but queries must merge multiple versions, adding read overhead.

Compaction: Background process that merges updates, applies delete bitmaps, rewrites column files, and reclaims space.

Apache Doris supports both MoW and MoR with configurable strategies per table, handling millions of upserts per second while maintaining query performance. The MoW approach is particularly effective for real-time analytics where read performance is critical. Benchmarks show 34x faster performance than alternatives for update-heavy workloads.

Can columnar databases handle joins?

Yes. Modern columnar databases support full SQL joins (inner, outer, cross, semi, anti). Common optimizations:

- Broadcast joins: Small table replicated to all nodes

- Shuffle joins: Data redistributed by join key

- Hash joins: Build hash table on smaller side

- Sort-merge joins: For sorted data

Performance tip: Modern columnar databases handle star and snowflake schemas efficiently. For frequently-run queries with complex joins, consider materialized views to pre-compute results.

Why are columnar databases faster for analytics?

The performance advantage comes from multiple compounding factors:

- I/O reduction: Read only needed columns (often 5–10% of table width)

- Compression: 5–10x smaller data to read from disk

- Vectorization: Process thousands of values per CPU instruction

- Cache efficiency: Homogeneous data fits better in CPU cache

- Predicate pushdown: Filter early, before expensive operations

- Late materialization: Avoid constructing rows until necessary

Each factor provides 2–10x improvement; combined, they deliver 10–100x speedups for typical analytical queries.

Conclusion

Columnar databases have evolved from batch-oriented data warehouses to real-time analytical engines handling semi-structured data at massive scale. The core insight (storing data by column to optimize analytical access patterns) remains constant, but the implementation continues to advance.

When evaluating columnar databases today, consider which generation of problems you're solving:

-

Structured batch analytics: Any columnar warehouse will serve you well

-

Real-time dashboards with sub-second latency: Look for real-time OLAP systems (Doris, ClickHouse, Pinot)

-

Semi-structured data with dynamic schemas: Evaluate VARIANT support and wide-table optimizations

-

Mixed transactional and analytical workloads: Consider HTAP capabilities and hybrid storage

The right columnar database isn't about finding the "best" one. It's about matching storage architecture to your access patterns, latency requirements, and data characteristics.